Fort Pitt Casting

A machine shop transformed into a greenhouse in the abandoned Fort Pitt Casting Company in McKeesport.

Losing a Foundry: Fort Pitt Casting Company

Updated August 6, 2019 | By Matthew Christopher

The last time I visited the Fort Pitt Casting Company was on an overcast afternoon in 2013, less than two years before it would finally be demolished. There was something charged in the air, that odd sense of kinetic energy that precedes a summer storm and gives you goosebumps in expectation of something you aren’t even entirely sure you can define. The former foundry’s long bays had turned to an unplanned arboretum, with weeds running rampant over dusty workshops and remnants of machinery in supersaturated explosions of green that glowed in the light. I had been there years before but something was different this time. The flora was swallowing the place, transforming what had once been a dirty old industrial ruin into a thing of wonder and beauty. As peaceful as it was, you would never have imagined the fire it had once contained, both in its operations as a foundry and as a hotbed of labor unrest.

Fort Pitt Casting Company had been founded by C.S. Koch in 1906 - a little over a century before my visit - on 13 acres that would become part of McKeesport, Pennsylvania. According to Jason Toyger’s fantastic and history of the plant on Tube City Online, “Fort Pitt made items for industrial customers, like pipe fittings and couplers for boilers and water systems; axle and bearing parts for railroad cars and locomotives; gears, hooks and chains for mines and factories; and pieces for large electric motors and circuit breakers.” Foundrymen would create a pattern for the desired steel or iron product, pack it in wet sand, and pour molten metal into the mold when it dried. Fort Pitt was smaller than many of its competitors but this worked to its advantage, allowing it to adapt quickly and keep costs low. They were innovators in their field, and relations between the management and labor were quite good for the time.

The camaraderie was short lived. In 1943 the plant was acquired by H.K. Porter Company, and the following January forty three of the welders went on strike, forcing all of the plant’s 1,300 employees to idle for two days. It was the first strike in five years, and both the unions and the company management were against it, but that July three hundred more workers were idled by thirty striking core makers over a delay in approving a back pay plan despite a vote by the union to return to work.

In 1945 there were more strikes. The Pittsburgh Steel Foundry Corporation purchased Fort Pitt and hoped to continue use of their facilities for production of electric steel products such as small carbon and alloy castings that would complement the Foundry Corp.’s manufacturing of electric motor frames and locomotive parts. Yet another nine day Fort Pitt strike occurred in 1954 over denial of a raise and pension/insurance improvements.

Brightly colored hard hats were a haunting reminder of the jobs lost when Fort Pitt closed.

By 1959, Fort Pitt was purchased by Textron Textron, an industrial conglomerate based in Boston. Their management was poorly equipped to handle Fort Pitt, strikes continued, and Fort Pitt’s competitive edge vanished as its equipment slowly grew outdated. By the 1970s Textron had sold Fort Pitt to another conglomerate that sold it again shortly thereafter to Condec Corporation, which was collecting small foundries to compliment its own.

It seemed like Condec would be a better fit to manage Fort Pitt than previous owners. They conducted studies on how to improve the plant for the future, moved in equipment from other facilities, and invested in updating production. Nevertheless, the poor relationship between management and labor continued and in 1974 there was yet another six week strike. Condec determined in 1977 that the plant was outdated, physically deteriorating, and unsafe. Operations were losing about $800,000 annually in the face of overseas competition. It would take an enormous investment to modernize the plant. Decades of resentment finally boiled over in 1978 when a strike dragged on for nine months and both sides refused to budge. Condec decided to close the plant in November of 1978, leaving hundreds of workers unemployed.

Less than a year later, a ray of hope emerged. With the help of an investment bank, the former workers planned to purchase and run the facility themselves as McKeesport Steel Castings. Aided by $2.3 million in federal and county loans and an investment from the city of McKeesport, an $8.5 million stock ownership deal was reached. Though many of the former workers were still without jobs, it was hoped that with labor/management difficulties out of the way and a new contract to produce parts for oil companies, operations would expand.

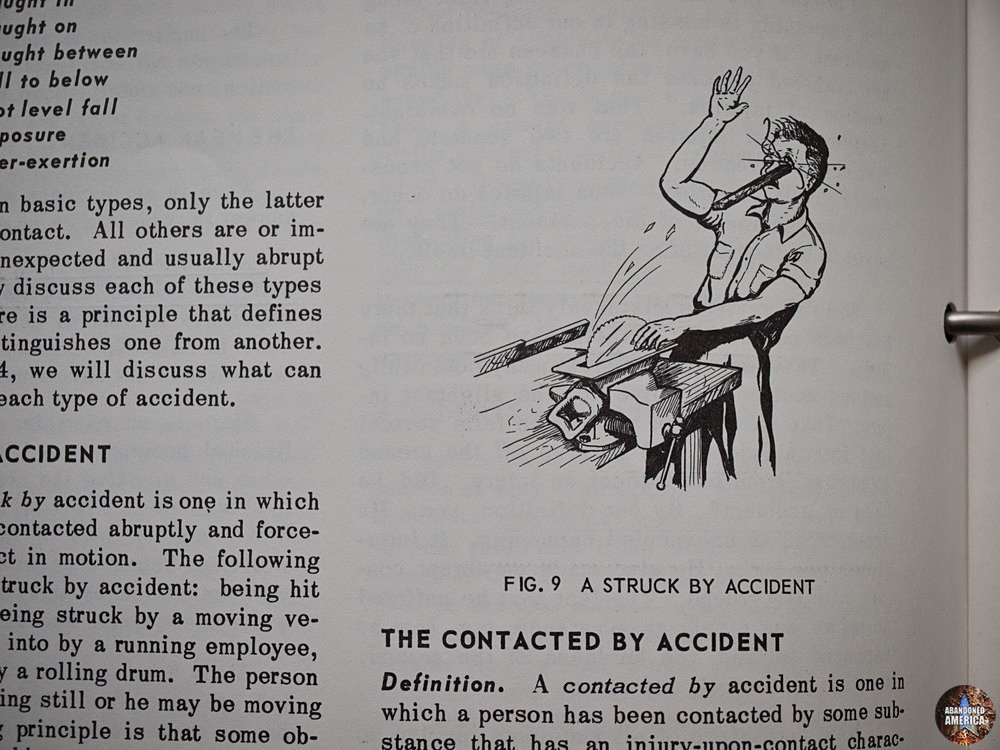

An industrial safety book found at Fort Pitt Casting Company is full of gory illustrations of work accidents that could befall careless employees.

The outdated equipment, poorly maintained plant, and overseas competition proved too much, though, and McKeesport Steel Castings continued to lose money. The company entered bankruptcy in 1983 hoping to restructure but a year later its production was minimal. It was purchased and renamed one more time, but swiftly closed for good when the utilities were shut off due to unpaid bills. McKeesport was already struggling economically and the closure was a tremendous loss from which the area still hasn’t recovered.

It’s always so hard in retrospect to pinpoint where a bond begins to deteriorate and why. It would be easy to place the blame entirely on the rotating array of managers or fickle, entitled union leaders and workers, but my guess is that simplifying it does both sides an injustice. The objective answers are likely gone forever now, or perhaps they never even existed. Like a marriage that starts with a mutual respect and degenerates over the years into bitterness and resentment, with each side feeling like the other is unreasonable and that their own needs are not being met, the resulting standoffs created vast chasms that ultimately proved too great to bridge.

I spent my days at Fort Pitt wandering through the aftermath, through crates still overflowing with colorful hardhats from decades ago and safety manuals filled with gruesome illustrations of the horrible fates that could befall the inattentive worker. The infirmary, where many life-threatening emergencies were surely treated, was filling with leaves, and in a nearby interior courtyard the railings were being engulfed by trees whose trunks were growing around them. I did my best to just observe and document the former foundry as best I could. When the inevitable rains came that final day, I stood for some time just watching the ripples and reflections in the steadily growing pools of water. You can’t always explain points in time that are magical, even when they are tinged with deep melancholy. Sometimes you just have to experience them them for what they are.

Fort Pitt Casting is a chapter in my book, Abandoned America: Dismantling the Dream.

Buy a signed copy via this link or get it on Amazon using the link below to read more!